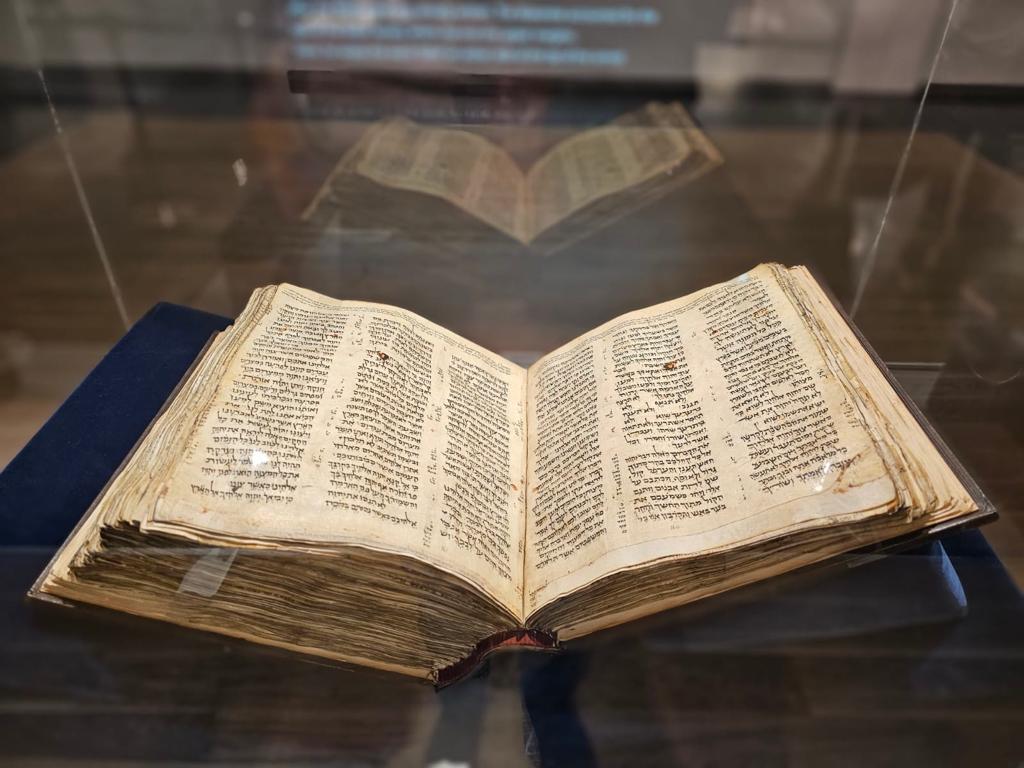

Codex Sassoon Eretz Yisrael, early 10th century CE Ink on parchment, modern paper, modern binding Gift of Ambassador Alfred H. Moses and his family to ANU Museum and the Jewish People

Text Panel

Codex Sassoon

It is a rare privilege to view a book that is more than 1100 years old. Codex Sassoon is the

earliest most complete Hebrew Bible extant, and it offers precious evidence of the history

and evolution of the Tanakh text.

Codex Sassoon contains all 24 books of the Tanakh, written on parchment sheets by a single

scribe and bound together as a book or codex. Unlike traditional Torah scrolls used in

synagogues, Codex Sassoon contains vocalization, punctuation, and cantillation marks.

Additionally, in the margins and between the columns of Scripture are notes about how the

text should be written and pronounced according to the tradition. These are called ‘Masoretic notes’.

Over the years, Codex Sassoon underwent several alterations that left their mark. Some of

its pages were lost, others were damaged, and it repeatedly underwent restoration. Today

the codex consists of 792 pages, which contain about 92% of the text of the Tanakh. It is

bound in a modern leather binding and weighs about 12 kilograms (26 pounds).

Codex Sassoon has been dated to the early 10 th century CE, based on the analysis of its

material components and graphic features. Examination of the Masoretic notes, dedicatory

inscriptions, and various repairs to the parchment until the end of the 14 th century yield the

conclusion that it was produced in the region of Eretz Yisrael and Syria, where it was also

preserved and repaired during the first centuries of its existence.

Subsequently, for hundreds of years, there was no trace of Codex Sassoon. During the past

century it was privately owned – until 2023, when it returned to Eretz Yisrael and was

entrusted to the ANU Museum, to safeguard it for the public.

Over the course of more than a thousand years, Codex Sassoon drifted from community to

community, locale to locale. Its fate was tied to the fates of those who produced it, shaped

it, and possessed it. It tells a story of tradition and creativity; of migration and displacement;

and of disappearance and rediscovery – like the story of the Jewish people itself.